When the Whale Approaches:

I first encountered the work of Keyvan Mahjoor while moving through the works of painters from around the world — searching, without knowing exactly what I was looking for. Among all the surfaces and gestures I came across, his drawings captivated me. There was something in the figures: not just their posture or delicacy, it felt like a secret world with its own metaphysical time.

I did not fully understand what I was seeing. However, the figures felt familiar, as if they belonged to my world as well. I knew I had to learn more — about them, and about the artist who gave them form.

An Interview with Keyvan Mahjoor on Time, Memory, and the Image

Written by Guzal Koshbahteeva𓂃 ོ𓂃

•••••

Originally from Isfahan, Iran, Keyvan Mahjoor has been living in Montreal, Canada, since the early 1980s. Over the years, he has been many things: a publisher, a migrant, and an artist. His recent drawings have appeared in exhibitions at Arta Gallery in Toronto, Dastan Basement Gallery in Tehran, and Dena Gallery.

•••••

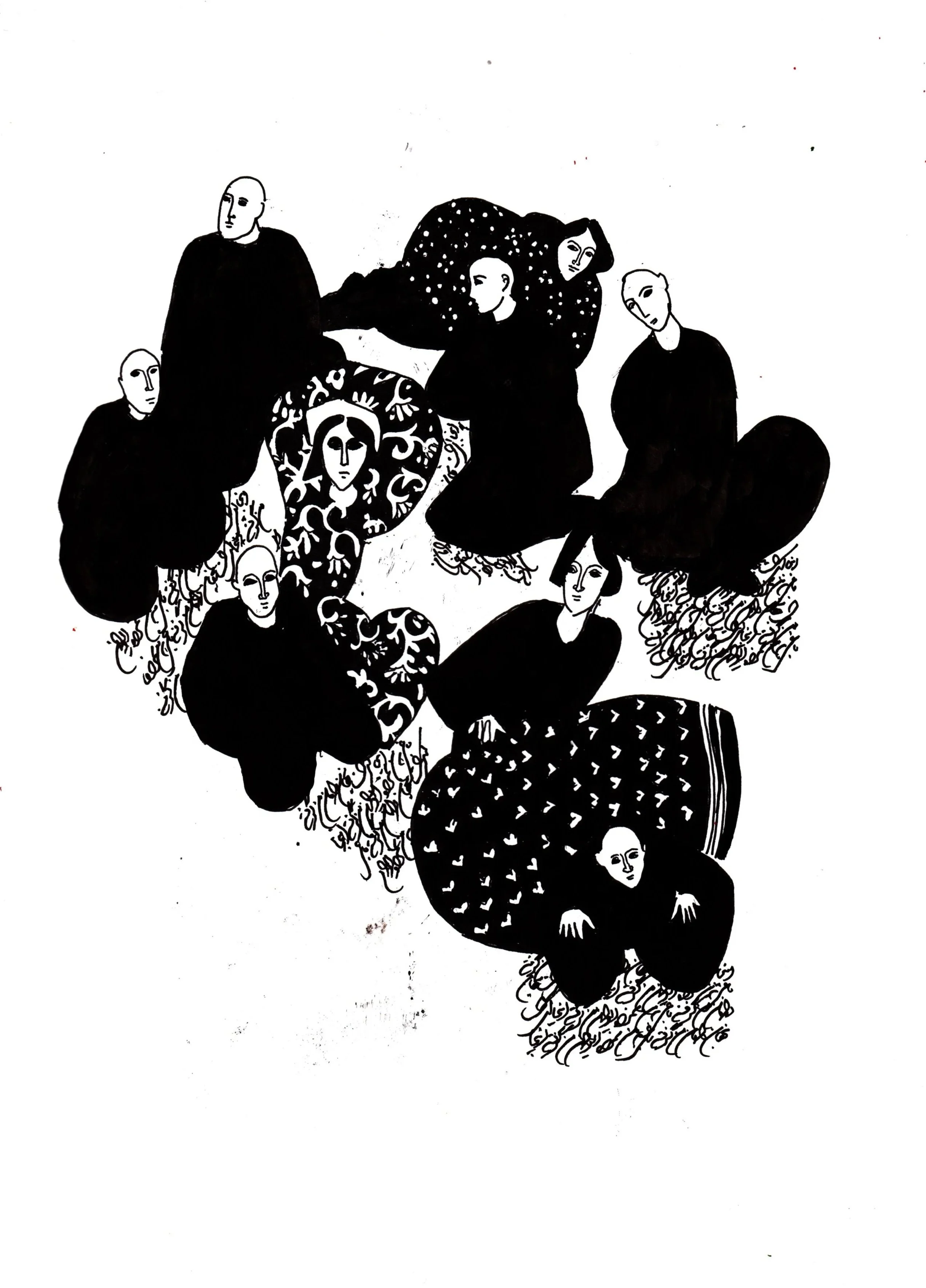

Keyvan Mahjoor draws every day: one painting, each day. Over the decades, this ritual has filled forty-five books, thousands of pages. Each drawing begins in chaos and gradually takes form, evolving into intricate miniature paintings. Through this daily act, Mahjoor constructs a private language of persistence and time, and perception.

When encountered closely, his drawings hold time in themselves. There is a complex, nuanced conversation between the figures he creates and the concept of time they inhabit. In Art and Time, Philip Rawson notes that “the word we use for time itself creates a central problem. The moment we begin to look into its meaning, we confront an abyss”(Rawson, 2005, p. 26). Keyvan Mahjoor’s work emerges from that abyss. His drawings begin in disorder, mirroring the uncertainty we face whenever we try to measure, understand, or define time. Nevertheless, through repetition, that uncertainty starts to take shape, and chaos finds a kind of rhythm. Furthermore, chaos becomes the place where time begins to exist.

To approach the concept of time in his work, one must consider the tradition of Iranian miniature painting, which offers an alternative to linear storytelling. There, it is not about one event leading neatly to the next; time unfolds not in sequence, it unfolds in parallel. Myth, memory, imagination, and the past and present coexist within a single visual field. This approach originates from ancient Iranian belief systems, particularly Zoroastrianism, which describes two distinct forms of time: Zurvan Akarana, the infinite and eternal time preceding creation; and Zurvan Dareghokhadāta, the kind of time we experience—finite, measurable, with a beginning and an end (Gololobova, 2017).

Mahjoor’s drawings do not directly cite this tradition, but they share its logic. The recurrence of his black and white figures and motifs is a visual rhythm through which each image becomes a reflection on time itself. Past, present, and imagined moments do not follow one another; instead, they coexist, creating a quiet tension. Therefore, his work engages with a pictorial thinking that resonates with the Iranian miniature tradition in this way. Time is not measured; it is layered, and his art bears it in itself. Like the miniature painters before him, Keyvan Mahjoor employs careful, repeated elements to bring something timeless into view, and by doing so, he creates a world of myth.

The ideas above are, at best, speculative translations of a visual language that does not ask to be explained. Interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art, Susan Sontag once warned (Sontag, 1966), and perhaps this entire introduction is already guilty. Therefore, to move beyond that impulse, I reached out to Keyvan Mahjoor, who has kindly agreed to share his work and perspective with me. As Trinh T. Minh-ha writes, it is often more meaningful and more respectful to stay nearby, to approach things by speaking close rather than speaking for (Trinh, 1989). On that note, the interview:

𓆝 𓆟 𓆞 𓆝 𓆟

𓆝 𓆟 𓆞 𓆝 𓆟

Guzal Koshbahteeva: First of all, thank you for taking the time to join this conversation and for your willingness to share a glimpse of your work and creative process. I’d like to begin by asking you to introduce yourself and speak a little about what you do, at your own pace. How would you define your work?

Keyvan Mahjoor: My name is Keyvan Mahjoor. I was born and raised in the city of Isfahan, Iran. The city has been the center of Persian arts and crafts for centuries. My first teacher and influencer was my mother, who had a fine ability to draw and paint, who encouraged me from an early age, and then sent me to a master of miniature painting to study that traditional style for four years. By the time I finished my high school years, I had realized that Persian Miniatures were mostly illustrations of literary concepts. To familiarize myself with the origins of these concepts, I went on to study Persian literature at Pahlavi University in Shiraz. The city that was the center of great poets and mystics of Iran. Those years were the ones in which I discovered my sources of inspiration.

Guzal: When you think of Isfahan, what comes to your mind first? What did your surroundings look like: the streets, the architecture, and do you think they still live somewhere in your line today?

Keyvan: Do you know, Isfahan has such a long and layered history? When I think of it, I think of what those streets carry. Zoroastrianism was once the official religion of Iran, and the Manichaeists were persecuted under it. Many fled to the Roman Empire, where they continued teaching. Saint Augustine, before becoming a Christian, was a Manichaeist. In City of God, he advised painting church walls with biblical stories, since most people were illiterate. However, the idea of telling stories through images originated from Manichaeism and Iran.

Iranian painting has long been associated with storytelling. And even today, in traditional cafés in Iran—or even parts of Europe—you can still see large paintings depicting stories from Shi’ism or Islam, with someone explaining the scene aloud. That’s a continuation of that tradition. As a child in Isfahan, my mother took me to a master of miniature painting. I was struck by how each painting illustrated a story. That experience shaped me. I realized: if I want to understand what to draw, I need to understand the literature.

So, I studied Persian literature to learn what lies within these stories. That’s where my own style began. From then on, I thought: Now it’s my story. That’s how it started.

Guzal: You mentioned how deeply Persian literature shaped your early artistic vision. However, I also found that literature has a practical impact on your life. You founded Ketab-e-Azad, a bookstore and publishing house. Could you tell me about how that came to be?

Keyvan: While I was studying in England, I had this idea to have a bookstore and publish the works of artists, like poets, painters, whose works are not being published in big companies because they are not famous enough. I thought I could help them… and begin publishing, at least a small number of publications, or limited editions. Then, to have an opening, invite people and promote it. This was my idea of freedom.

Guzal: There’s something generous in that vision; in creating openings for others, even in small editions. And I wonder if that same attentiveness shows in your drawings, too. Your work carries a delicate, almost tender quietness, a silence that seems to move, as if the figures you draw are waiting for something unseen. It feels like that silence belongs not only to the image, but also to the hand that draws. How do you understand this stillness? Could it be, in some way, a language of its own?

Keyvan: Persian miniatures are defined by their fine lines and extreme delicacies in the treatment of the subject of the painting. The silence, of course, comes from the meditative act of drawing those fine lines. The great role of mysticism is evident in every aspect of Persian art, from poetry, the highest form of Persian art, to painting, architecture, and writing. Yes, you are right, it is the language of meditation.

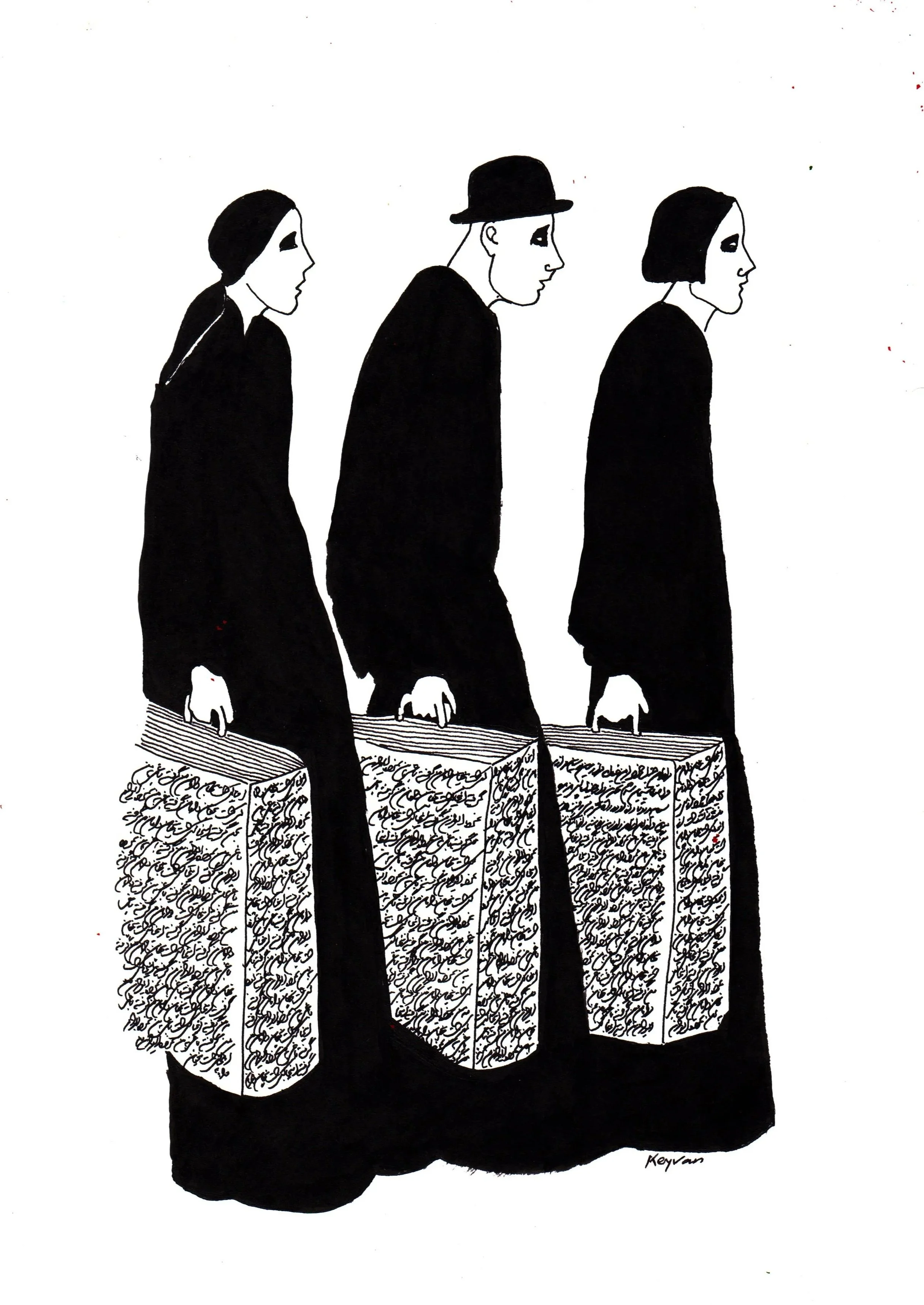

Keyvan Mahjoor©

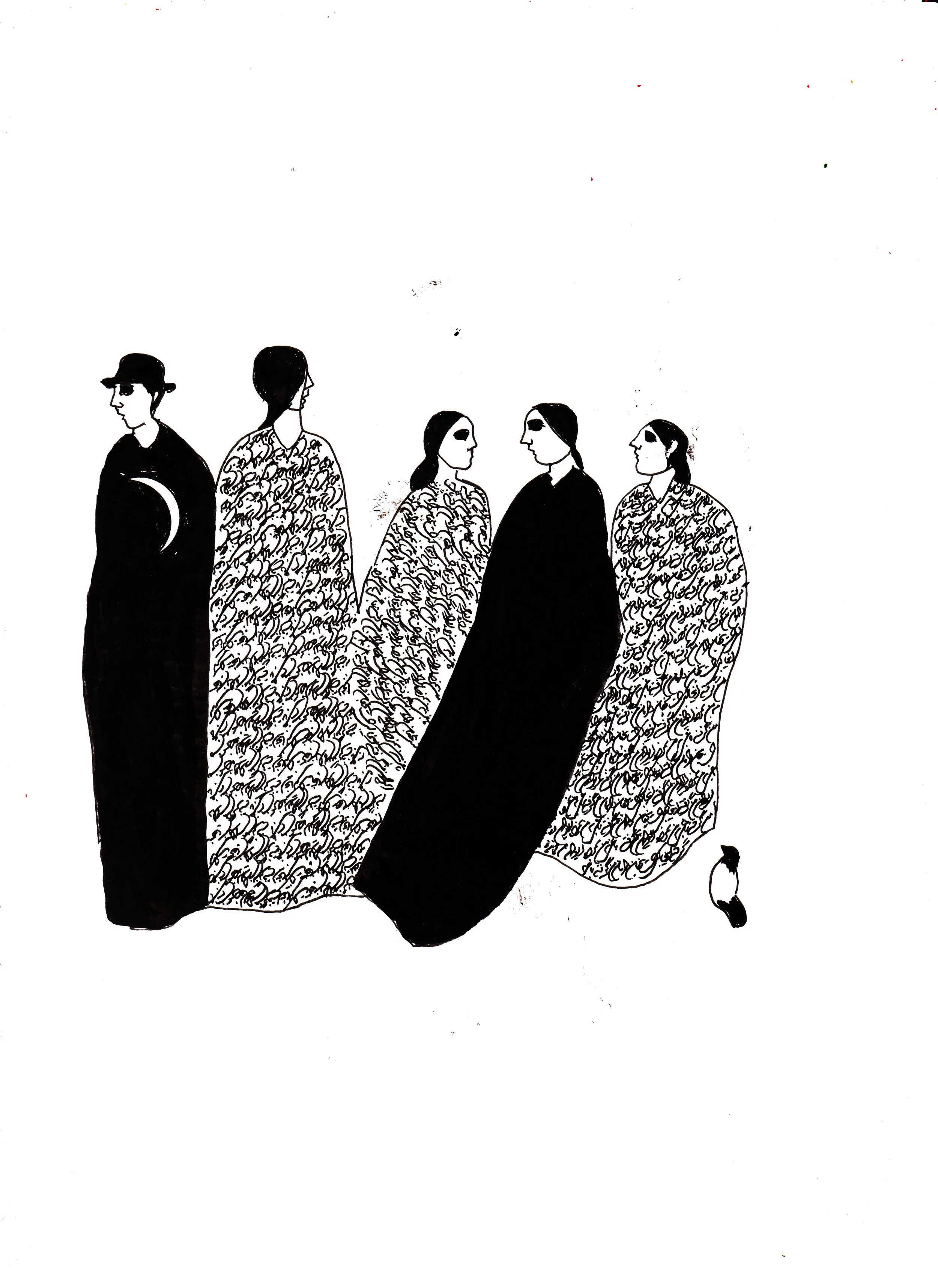

Keyvan Mahjoor©

Guzal: The link you draw between mysticism and form lingers. It makes me think of how, in your drawings, presence becomes almost atmospheric. I sense the rhythm of contemplation within your images. I would also note that the surface of your drawings feels like a living field with presence, reflection, and language. Moreover, time is layered within them: the present, the remembered, and the imagined. Do you experience these dimensions as separate, or do they unfold together when you work?

Keyvan: Almost all Persian miniature perspectives are bird-eye view, so if in any of my drawings one sees an illusion of perspective happening, it is the treatment of lines and nothing else. As I mentioned earlier, most Persian Miniatures are illustrations of literary texts, so they usually come with the text attached. My texts are not readable even for Persians. They are there to claim their place rather than comment on the image. They are my daily meditations.

Guzal: Looking at your work, I find that the figures seem to recall something older than themselves, as if memory precedes the image. Do you see your work as a meeting point between your own memories and the deeper cultural memory of a civilization still dreaming through you? Or could you describe this relationship of memory throughout all your work?

Keyvan: You are right — the figures are a combination of memory and present-day acquaintances. Since I left Iran in 1981, I decided to do one drawing a day in a book. Now I have 45 books, each with 365 drawings. Each one includes a note about what happened that day and how I was feeling. I don’t know — it’s for others to say whether they see traces of that culture in my work or not. That’s how I feel about my past, my present, and how they are reflected in my work.

Guzal: Would it be wrong to say that your true medium is time itself?

There’s a clear relationship with it in your work; the discipline of drawing every day, the forty-five books that hold those moments. However, within each drawing, there’s also a sense of another time that doesn’t belong to the present, a kind of time filled with longing, mystery, even bewilderment. How do you perceive this interval between the time contained in those books, the time you live in now, and the time depicted in your drawings?

Keyvan: Yes, I agree. Because it really depends on the moment—what day, what year—I worked on something. That becomes the feeling behind it. Even if there are recurring elements, the story is always mine. I am the same person, but each drawing reflects a different moment.

Some elements come from the past, some from the present—sometimes even from dreams. The characters that appear in my work, the serious figures—they are my parents, or people like them. They stay with me. Their stories are still with me.

The city I come from is full of those designs—the mosques, the carpets, the textiles. I can’t escape them. They’re like a dream I carry. But I reduce them, simplify them. I might only use a fragment. Take Persian calligraphy. The alphabet is Arabic, but we transformed it into something else. We invented styles like Shekasteh and Nasta‘liq Shekasteh—forms so uniquely Persian that even Arabs can’t read them. I use that in my drawings.

Guzal: It is interesting. In a way, it is your secret language. Would you agree?

Keyvan: It becomes a kind of secret language. The text is unreadable, but something is still being communicated. It mystifies the drawing. In traditional miniature painting, you always had writing around the image—but in mine, you can’t read it. That mystery, that unspoken part of the story—that’s what I’m using now.

Guzal: That’s beautiful — but it also sounds like an immense amount of dedication. You’ve been drawing one piece each day; when did you begin this practice?

Keyvan: Since I was 18, when I got serious about it at university. And yes, I’ll make one today, too.

Guzal: And how long does it usually take?

Keyvan: Not very long. I start with total chaos. Then I reduce — reduce my lines, refine the form — until I reach the point I’m looking for. Once I get there, it’s easy. The chaos tells me what’s behind my mind.

Guzal: It may seem like a small question, but I wonder what memory is for you? How do you understand it in your life and work?

Keyvan: It comes to me when I’m searching for a story to tell. I believe the highest form of art in our time is storytelling. If you have a story, tell it — like Shahrazad in One Thousand and One Nights, who was sentenced to death but told stories each night to the Sultan to delay her execution. She postponed death by weaving tales. That, to me, is the power of storytelling: it keeps us alive. Silence, in comparison, is surrender.

Flight of Monochrome Feathers. Keyvan Mahjoor© Film by Arash Akhgari©

Guzal: That sincerity of storytelling is felt in your drawings. It also makes me think about what we choose to reveal and what we keep hidden. When you work, is there anything you consciously avoid — a feeling, a thought, or perhaps a part of yourself?

Keyvan: No, I do not. Sincerity is the essence of the arts. One must tell the truth about their story, even if it is the most difficult thing. We happen in this universe once! Why not tell the true story about ourselves?

Guzal: Could you tell me about your favorite story? How did it inspire you?

Keyvan: I’m more interested in the concepts than in any one story. But there is one story that I keep returning to — Jonah.

You’ve seen the fish in my drawings. I’ve done two paintings based on this idea. I play games with the story of Jonah because it fascinates me — he’s the only prophet who was, in a way, defeated by God.

He went around warning people: “You’re committing sins, and God is going to punish you. He’ll destroy you.” That was his message. Then, the story goes, he boards a ship. He talks about this so much that people throw him into the water. A wave comes, carries him to shore, and saves him.

On the day God is supposed to punish the sinners, nothing happens.

People mock Jonah. He goes to God and asks, “Why didn’t you punish them?” And God replies, “Did you really believe I would destroy them? I love them. I said those things so they would stop doing harm. But now that they have, I won’t destroy them.” Jonah becomes depressed.

I’ve always loved this contradiction — this failed prophecy, this moment of unexpected mercy. I’ve modernized it in my own way. One of those paintings is very recent — it’s on the top of my Instagram, in the highlights. Jonah is lying down, and a small whale approaches him. To me, it’s like he’s raising whales for the future.

The other painting is one of my favorite color works. It’s inspired by a couple — a Jewish couple — who lived above a synagogue workshop. Every Saturday, they invited me to join them for breakfast. I’d go, and while we ate, people would gather in the synagogue below, singing the most beautiful songs. That experience became a painting. In it, both of them appear. The husband is in the mouth of a large ship. I call the piece Ineb and Jonah at the Base of Jerusalem.

I love that kind of story, and it is not because it’s symbolic or grand, but because it’s personal. If I meet someone, and we share something, and their story moves me — it comes into my painting.

Guzal: When I first saw your drawings, it felt like entering the night or twilight, the most mysterious time or a place. It felt like shadows began to think. The moon, sleep, and calligraphy appear as states of being. How would you describe this state?

Keyvan: That is exactly the result of images coming out of a chaos of lines on paper to tell me and then you the story of that particular day, reminding us of the chaos of a universe that for only once every one of us is part of it.

Keyvan Mahjoor©

Keyvan Mahjoor©