Bukhara, Briefly: Misunderstanding as Method — Photography of Behzod Boltaev

Written by Guzal Koshbahteeva

**********

The photograph of a centuries-old pool in Bukhara shows boys gathered in the heat of summer, diving and resting around the water. In the lower corner, a boy reclines along the edge, his body stretched out, lying in a posture resembling a classical statue. His stillness is countered by other boys caught mid-air, diving toward the green water. On one hand, the photograph is a record of a simple moment of leisure: boys cooling themselves off under a summer sun. On the other hand, the image offers an alternative way of seeing the city. Bukhara does not appear to be fixed or frozen, as it is often portrayed in Orientalist representation; it is a living space. It is depicted as activated by movement, shadow, color, and play.

Photograph by Behzod Boltaev©

This way of seeing belongs to Behzod Boltaev, the photographer, rooted deeply in the city’s rhythms. Following in his father’s footsteps, he has been documenting the day-to-day Bukhara. Rather than documenting monuments or offering the familiar postcard image of Bukhara, he turns to his intimate knowledge of the place. Bukhara does not appear to be a relic of the past in his photography. It reveals itself as a city where the past is carried into the present, becoming part of everyday life and not a distant memory.

Looking across Boltaev’s work, one begins to recognize a method: boyhood, or youthfulness, as a stance toward the world. If one returns to the image of boys and the pool, the method is visible in the angle of the shot, the colors, and the space. Boyhood cannot be mistaken for the nostalgia of a lost age or ancient times; the photographer makes a stance toward the curious. His photographs oppose the stillness that often defines images of Bukhara and show a city in motion.

This puts Boltaev in conversation with the very medium he uses. In her book On Photography, Susan Sontag says, “all photographs are memento mori” (p. 15). “To take a photograph is to participate in another person's mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt" (Sontag, 1977, p. 15). This tendency toward stillness is built into the medium itself. Boltaev's work follows this logic; the diver above the pool is frozen and suspended. Simultaneously, the photograph has the power to seduce the viewer. In Bolyayev's image, the diver suspended mid-air is a form of visual poetry. Here, the water represents not just water; it becomes an emblem of vitality and youth.

That being said, it is not a contradiction of Sontag's point. This argument is an extension. The slice of time carries with it an excess of meaning. The photograph of boys swimming on a summer day becomes more than a documentation. The image seduces precisely because it exceeds its occasion and becomes visual poetry. Boltaev's contribution lies in working with this condition and not against it. He accepts that the camera freezes time and finds an openness within that stillness. The moment feels unfinished, as if it asks the viewer to help complete it. In this way, his method of youthfulness is his way of seeing. He allows a photograph to hold the world in suspense and, like youth, lets it be in the process of becoming.

This sense of youthfulness also becomes a counter-aesthetic. It accepts the stillness of the medium and, at the same time, refuses to let it harden the city into a monument. The image stays open because it is shaped by the photographer's timing and the convergence of city, body, and chance. John Berger (1972) writes that seeing is not neutral; each photograph carries the weight of social life and reflects what Bukhara offers back to the lens. (Berger, 1972) If one were to look at Boltaev's other images, the same pattern would appear: ordinary gestures turned poetic, moments less about technicalities and more about encounters. A drum is thrown into the air, a wall seems to watch over a female passing by, boys’ silhouettes running over the city monuments, and a boy with a hen on his shoulders. All of these instances gather meaning from the interplay between subject and setting. What is more, these images serve as reminders that photography is an act of taking and receiving, a negotiation between what is before the lens and what exceeds it.

Photographs by Behzod Boltaev ©

Some photographs in Behzod’s work move with a different rhythm. Beyond the energy of daily life, there are images that hold stillness, inviting the viewer into a quieter form of engagement. These scenes emphasize presence through detail, light, and the subtle relationships between elements in the frame. Meaning begins to unfold through atmosphere rather than motion. Such moments depicted in photographs open a space for reflection, interpretation, and a way of seeing that lingers with what cannot be easily resolved.

Misunderstanding: Heaven?

Photographs are often thought to share information, feelings, or perspectives with the viewer. Today, they have become part of our daily experience. However, there is a question that always remains: do we truly understand a photograph, or do we not? Misunderstanding may not be a failure; it could be a beginning. We like to believe the camera fixes truth, sharing with its viewers an exact account of what stood before it. In reality, every photograph contains more than it intends, and not all is clear. A shadow stretches without a body, a branch intrudes into the frame, a reflection unsettles the line between figure and ground. We think we see one thing, meanwhile, the image quietly carries us elsewhere.

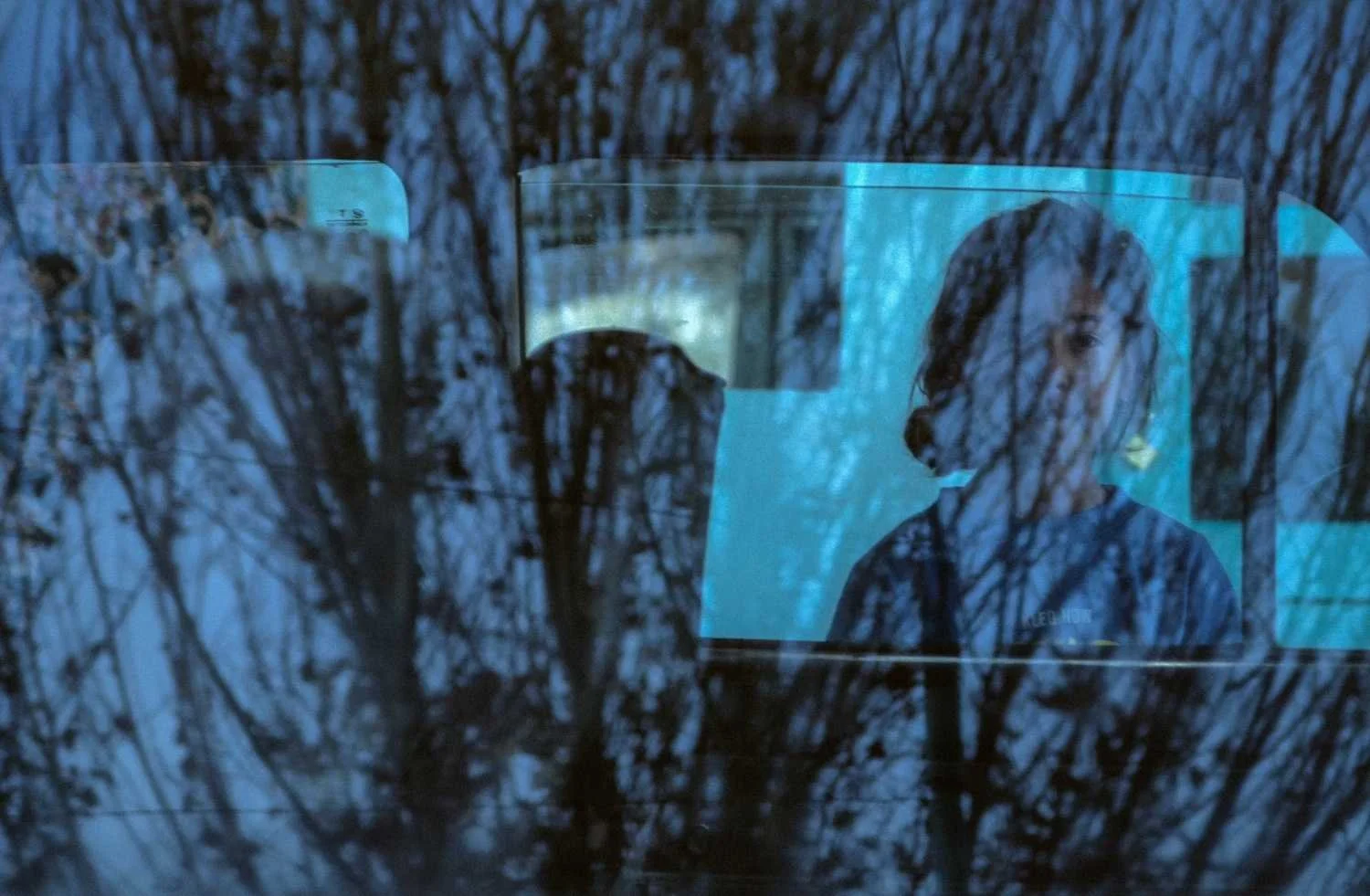

In the following photograph, Behzod captures what he titled Heaven. A girl is looking back into the camera from behind the glass of a car window. Her face is half visible, her gaze direct, and nothing in the composition is especially obscure. Shadows of tree branches fall across the glass, the color of blue appears twofold—of the sky and the wall behind it.

Heaven, Photograph by Behzod Boltaev ©

Perhaps the first impression the viewer can realize is that the photographs carry a quiet poetry. There is a gentle interplay here between the innocence of the child and the innocence of nature, between the gaze that returns to us and the dappled shadows of tree branches. It would be difficult to call the photograph obscure, for its elements are plain enough, while also feeling delicate and poetic.

The questions begin when we try to interpret the image: Is the blue sky only a reflection? Do the branches belong to her world or ours? The photograph opens a field where meanings can be misleading because interpretation is never stable, while the photograph's subject was—and is—clear throughout.

The title Heaven both intensifies and confuses. Without it, viewers might simply notice the girl's gaze and the branches on the glass. With it, we are steered toward blue sky, innocence, and the promise of elsewhere that exists beyond the car window. This is where the title misleads. Is Heaven present in the image, or is it only a color, shadow, or surface we want to believe in? The photograph works between clarity and suggestion, showing that its mystery lies not in the subject but in what the audience brings to it.

Heaven shows that a photograph can become mysterious through abundance rather than concealment. The glass surface, the reflections, her gaze, that field of blue, the word Heaven itself — there is more than we can easily assemble. The viewer must supply connections, misread, and reinterpret. What lingers in the image is her steady gaze, surrounded by the associations it quietly sets in motion.

Simultaneously, misunderstanding then becomes a kind of imagination: the viewer fills what the photograph leaves open. As John Berger (1972) writes in The Ways of Seeing, “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled. Each evening we see the sun set. We know that the Earth is turning away from it. Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight”(Berger, 1972, p. 7). The gap between seeing and knowing shall not be seen as weakness but rather a recognition of how art and life meet. Furthermore, it is in this gap that the meaning is created. Heaven works in this way, by withholding resolution so the meanings emerge via the effort to imagine and to live with ambiguity.

Boltaev's photographs return Bukhara to us as something lived rather than displayed or preserved. The pool shows a body mid-action, and the scene carries the weight of heat and movement. Heaven shows a face behind glass, shaped by a title and a color that do not fully resolve. In both works, time feels open, and the images ask the viewer to return and look again.

As Paul Valéry observed of poetry, "A poem is never finished, only abandoned" (Valéry, as cited in Ratcliffe, 2017). The same could be said here, because the photographs point beyond themselves. Each image suggests there is more to the city than what is shown—more to the artist than what can be captured in a single frame.

Photograph by Behzod Boltaev ©

Closing thoughts:

There are a couple of questions left lingering, and they may be the most important ones: Do we ever truly finish seeing a place, or does it continually escape our gaze? And what if misunderstanding is not a flaw but a form of intimacy with the unknown?

**********